Distributed Systems, for fun and profit: Part 2

With the basics and idea of abstractions covered in the previous post, we move on to the fundamental topics of time, order and replication mentioned in the text

Time and Order

Order is a way to define correctness or “it works like it would on a single machine.” All operations can be arranged in the way they came (total order) by timestamp’s using an accurate clock or some kind of communication to establish the sequence. But in distributed systems, communication is expensive, and clock synchronization is difficult. The natural state of a distributed system is partial order, some pairs of elements are not comparable, while total order requires an ordering for every element. Git branches can be an example for partial order, where branches A and B, from a common branch, have an ordering until the split. After this, there is no defined order between them. Nodes in a distributed system may have a local order, and these are independent of each other.

Time is a source of order, attach timestamps to events and order them. It can also be interpreted as a universally comparable value or a duration (which hold importance in applications, eg. waiting period) from the start till now. Although it is easier to assume operations arrive one-after-the-other than arriving concurrently, such strong assumptions lead to fragile systems. Possible timing models based on the nature of clocks are:

- Synchronous system model (time with global clock): Clocks of nodes are perfectly synchronized (start at the same value and don’t drift) is an idea of the global clock (source of total order) and all nodes having access to it. They can determine order without communication. Cassandra assumes clocks are synchronized and uses timestamps to resolve conflicts. Spanner uses an API to synchronize time also determines the worst-case clock drift.

- Partially Synchronous system model (with a local clock): A more likely scenario with a local clock with each node. This means that we cannot meaningfully compare timestamps from 2 different nodes. Partial order: events at nodes are ordered, but events across the node cannot be ordered using a clock.

- Asynchronous system model (no clock): No clocks to provide timestamps, but we can use counters and communication to determine if relative order. Although the order can be determined, intervals or duration cannot be measured. This also has partial order (event across systems required communication), and Lamport and vector clocks are ways to track causality (which event caused another) without using clocks.

Time can be used to define the order (without communication) and boundary conditions (decision whether node is down). Lamport and vector clocks are replacement for physical clocks that rely on counters and communication.

In Lamport clocks, each process maintains a counter. When a process does work, the counter is updated and includes its counter value when it sends a message. While receiving, it sets its counter to max (local, received) counter. If the timestamp on event A < timestamp on B then it can mean a happened before b or they are not related (Eg. in the figure below even though A has a greater timestamp/counter, A happened before B in global time. As they are not causally related they cannot be compared based on timestamps.); thus, it establishes partial order. Events A and B have the same causal history if they originate on the same process (one after the other) or one is a response to msg sent by another process.

p0: -- -- C (0) -- -- -- A(1) -- --

p1: -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- B(0)

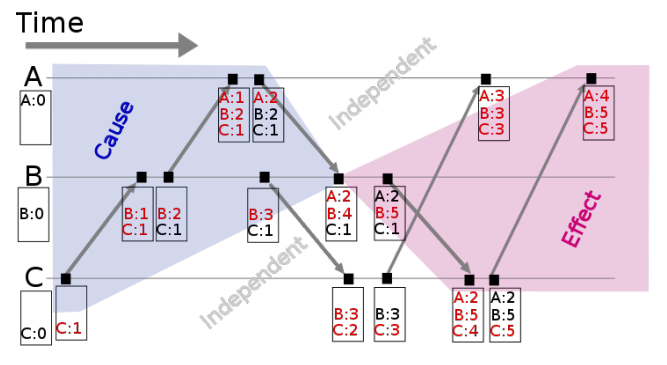

Vector clocks extend Lamport clocks and maintain a array of logical clocks (one for each node/process). If a process does work, it increments value in its corresponding position. It sends the array when communicating and when receiving a msg, it takes max of local and received values for all elements in the array and increments its counter. This allows for accurately identifying the messages that potentially influenced the event. Event timestamped with {A: 2: B:2, C:1} has probably been influenced by the messages from B and C.

Another important question is, what is a reasonable amount of time before we decide something has failed or is just experiencing high latency? Rather than putting specific values in the algorithm, we use a failure detector (to abstract away the exact timing assumptions). Failure detectors work on heartbeats and timers. If the heartbeat is not received within a duration, timeout occurs and the process is suspected. This kind of failure detector based on timeouts can be aggressive (suspect many processes) or conservative (take too long). So characteristics of Completeness and Accuracy are used to determine is a failure detector is usable.

- Strong Completeness: every crashed process is suspected by every correct process

- Weak Completeness: every crashed process is suspected by some process

- Strong Accuracy: no correct process is ever suspected

- Weak Accuracy: Some correct process is never suspected

Completeness is easier to achieve than accuracy. Weak completeness can be converted to strong by letting that process send a broadcast to others. A very weak failure detector (weak completeness and accuracy) can be used to solve consensus and certain problems are not solvable without failure detector (as node failure and network failure become indistinguishable). This was shown in the paper Unreliable failure detectors for reliable distributed systems. We would like to have a failure detector that adjusts to network conditions (rather than fixed timeouts). Cassandra uses a failure detector that outputs a suspicion level so the application can make its own decision (trade-off between deciding early and being accurate).

Time and order have an impact on performance; communication and waiting impose restrictions on how many nodes can do work. Algorithms care about causal ordering of events, failure detection, consistent snapshots (ability to examine the state at some point of time) rather than time. The decision for a system to use time/order/synchronization depends upon the guarantees it provides and if costs associated are acceptable. Synchronization is often used on all operations when required only for a subset.

Replication

Replication is a group communication problem. We need to find an arrangement and communication pattern to give us availability and performance desire as well as make it fault-tolerant, durable and non-divers during network partitions or node failures. This can be explored as independent patterns.

Synchronous replication involves the client sending a request after which the server responding syncs itself with other server and then responds to the client (write N-of-N). The performance of this systems depends on the slowest server and the system is sensitive to changes in network latency. It cannot tolerate server failures as then the server cannot write and only provides read-only operations, thus provides a very string durability guarantee. In Asynchronous replication, the server immediately responds to the client and syncs up in the background (write 1-of-N). This provides low latency to the client, more tolerant to failures, but provides weak guarantees (if that server goes down before sync). Also, if writes are accepted at multiple locations, this can possibly lead to divergence.

When you wait, you get stronger guarantees but worse performance.

Another way to look at replication methods is to prevent divergence and the ones that risk divergence. Single copy systems behave like a single system, ensures single-copy during failure and replicas are always in agreement. This is achieved via consensus, with methods like mutual election, leader election, multicast, atomic broadcast, etc. These single-copy replication algorithms (primary/backup, multi-paxos, 2pc, etc.) vary in fault-tolerance, and no messages exchanged. The other type (multi-master systems), which risks divergence, acts like a true distributed system consisting of multiple nodes. They give a way to reason about the characteristics that they have. Examples are client-centric consistency models, CRDTs, etc. and are discussed be seen later.

Single-Copy Replication / Strong Consistency model Protocols

In Primary/Backup replication, all updates are performed on the primary and a log of operations/changes are shipped across the network to the backup replicas. This can have asynchronous (used in MySQL and MongoDB) and synchronous. Failure scenarios are present in both settings (primary fails the latest operations not backed-up are lost), and they have weaker guarantees provide “best-effort service.” They are also susceptible to split-brain (backup becomes primary, due to temporary network issue, causing two primary to be present).

Two Phase Commit (2PC) is used in MySQL clusters with synchronous replication. In the first phase, a coordinator sends an update to all participants and each participant votes on whether to commit or abort. Updated is stored temporarily until the second phase, in which the coordinator decides the outcome and informs participants to make it permanent or discard (allowing rollback). Node failures block progress until all nodes have been discovered and thus, it is also not partition tolerant.

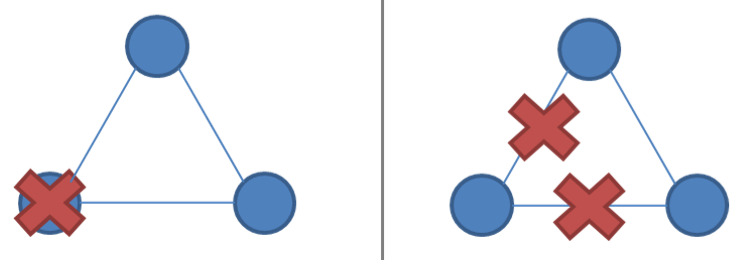

Partition tolerant consensus algorithms The system is divided during a network partition and it can be similar to node failure, thus difficult to identify as shown in the figure below, and both sides are accessible to the client. Therefore to ensure single-copy consistency, we require to distinguishing these two so that one side remains active.

Thus, these algorithms rely on majority voting, requiring a majority rather than all allows minority no of nodes to be down or slow or unreachable. If (N/2 + 1) of N nodes are up, the system continues to operate and also they use N as odd (3, 5, 7, etc.). Such a system with N nodes is resilient to failure of N/2. During a partition, one partition contains the majority of nodes; the minority partition will stop processing to prevent divergence.

Nodes in such a system may have the same or distinct roles. Consensus algorithms for replication generally have distinct roles, having a leader through which all updates pass, makes it efficient. The leader/proposer coordinates which the rest are followers/acceptors/voters. These terminologies are using in Paxos or Raft. Each period of normal operation in Paxos and Raft is called an epoch, in which one node is a designated leader. A successful election in an epoch result in that leader to coordinate until the end of the epoch, else the epoch ends. Epochs act as logical clocks, allowing to identify nodes that are partitioned, OOO, etc. with their epoch numbers being smaller. All nodes start as followers; they initiate leader election (at random times) and get elected with they receive a majority of the votes (if followers receive an election message they accept the first one). Proposal/updates by clients get relayed to the leader by follower nodes. The leader proposes a value (if no other proposals exist) to be voted upon. The value is accepted if the majority of followers accept the value. This is the idea behind the consensus algorithms and each of them their own protocol along with many optimizations. There were other details in the text that were not clear to me. I will try to write about consensus algorithms when exploring them in detail. Examples of these consensus algorithms are Paxos (used in Chubby, GFS, Spanner), ZAB (Zookeeper atomic broadcast used in Apache Zookeeper) and Raft (used in etcd).

Weak Consistency model Protocols

Strong consistency guarantees require enforcing some order and require contact with a majority of nodes (communication). This can be expensive and possibly not desired in systems geographically distributed that do not want expensive communication and yet want a correct value. Eventual consistency models allow nodes to diverge but eventually agree on the value. Systems providing eventual consistency can be of two types. Eventual consistency with probabilistic guarantees can detect conflicting writes but does not guarantee that the results are equivalent to sequential execution. In Eventual consistency with strong guarantees, the results converge to some correct sequential execution. During a partition, the divided replicas can accept both read and writes from the client. When the link is up again, they can communicate again to exchange information for reconciliation (hopefully getting the correct and same order of operation).

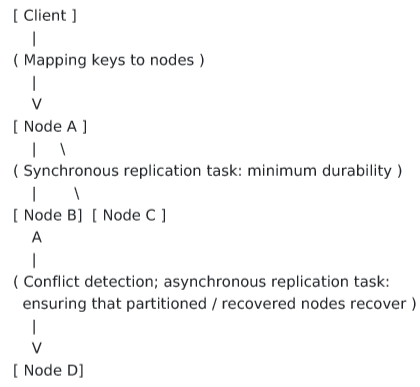

Amazon’s Dynamo is an eventually consistent key-value store that provides weak consistency guarantees with high availability, an example of a system with probabilistic guarantees and an inspiration to LinkedIn’s Voldemort, Facebook’s Cassandra, etc. It consists of N peer nodes with each node having a set of keys. Dynamo allows replicas to diverge when keys are written, putting availability over consistency. During reads, there is a read reconciliation phase to reconcile differences before returning the value. We now explore how a write is routed to multiple replicas

Clients locate which node is responsible for a key mapped using Consistent Hashing (helps distribute keys to nodes uniformly). Now the node getting the request has to persist the value, and this is done synchronously to provided durability (protection from immediate failure). Like Paxos and Raft, Dynamo uses quorums for replication but they are partial. They do not require a majority vote and different subsets of the quorum may contain different versions of the same data. Users can choose W-of-N nodes for a write to succeed and R-of-N nodes to contact during read.

It is recommended that R + W > N so that the nodes in the sets overlap to make it less likely to return stale value. If R = 1 and W = N, we get fast reads and slow writes, and such similar results can be deduced. N is typically 3 and Cassandra uses R = 1 and W = 1 while Voldemort uses R = 2 and W = 2 as default. While R + W > N does make sure the latest values come to read, it does make mean its strong consistency as nodes in the clusters can change (during node failures, new unrelated nodes are added into the cluster). Also, during network partitions, it allows wite on both sides.

For the reconciliation of diverging replicas, one way to solve is to detect conflicts at read time and then apply a conflict resolution method. This is done by tracking causal history of a piece of data with metadata. Clients, when reading, use store this metadata and while writing, send the metadata. Vector clocks (keeping the history of a value) were used in the original Dynamo to detect conflicts. Other ways can be no metadata (last writer wins), timestamps (higher timestamp value wins) and version numbers. With vector clocks, concurrent and out of date updates can be detected and repair becomes possible (in case of concurrent changes it does need to ask clients). While reading a value, the client contacts R out of N server and gets the latest value for the key, discarding values that are strictly older. If multiple vector clocks and value pairs are found, they have been edited concurrently; hence all of them are returned (Since no example is given I found it difficult to understand what is actually happening. I will try to write about it when understanding Dynamo). When returning from failure, node synchronize using gossip (every t seconds contacting a node) and Merkel trees to compare their data store contents efficiently.

Other topics discussed in the text following this are:

- probabilistically bounded staleness: to estimate the degree of inconsistency in systems like Dynamo

- disorderly programming: if types of data types are known then handling conflicts become easier

- CRDTs (Convergent Replicated Data Types): exploit knowledge about commutativity and associativity of specific operation (for max order does not matter) and data types

- CALM theorem, monotony: logically monotonic programs (a deduced result from a known fact cannot be invalidated) are guaranteed to be eventually consistent These are excellent topics but may get a bit complicated thus, I feel they were not necessary for this overview of distributed systems. I’ll try to write about them when I dive deeper into distributed systems.

Note

- Please let me know if I misinterpreted or missed something or any top requires more clarification.